আপনাদের পড়ার জন্য হবহু কপি করে দিলাম।

The Coming Storm

The people of Bangladesh have much to teach us about how a crowded planet can best adapt to rising sea levels. For them, that future is now.

By Don Belt

We may be seven billion specks on the surface of Earth, but when you're in Bangladesh, it sometimes feels as if half the human race were crammed into a space the size of Louisiana. Dhaka, its capital, is so crowded that every park and footpath has been colonized by the homeless. To stroll here in the mists of early morning is to navigate an obstacle course of makeshift beds and sleeping children. Later the city's steamy roads and alleyways clog with the chaos of some 15 million people, most of them stuck in traffic. Amid this clatter and hubbub moves a small army of Bengali beggars, vegetable sellers, popcorn vendors, rickshaw drivers, and trinket salesmen, all surging through the city like particles in a flash flood. The countryside beyond is a vast watery floodplain with intermittent stretches of land that are lush, green, flat as a parking lot—and wall-to-wall with human beings. In places you might expect to find solitude, there is none. There are no lonesome highways in Bangladesh.

We should not be surprised. Bangladesh is, after all, one of the most densely populated nations on Earth. It has more people than geographically massive Russia. It is a place where one person, in a nation of 164 million, is mathematically incapable of being truly alone. That takes some getting used to.

So imagine Bangladesh in the year 2050, when its population will likely have zoomed to 220 million, and a good chunk of its current landmass could be permanently underwater. That scenario is based on two converging projections: population growth that, despite a sharp decline in fertility, will continue to produce millions more Bangladeshis in the coming decades, and a possible multifoot rise in sea level by 2100 as a result of climate change. Such a scenario could mean that 10 to 30 million people along the southern coast would be displaced, forcing Bangladeshis to crowd even closer together or else flee the country as climate refugees—a group predicted to swell to some 250 million worldwide by the middle of the century, many from poor, low-lying countries.

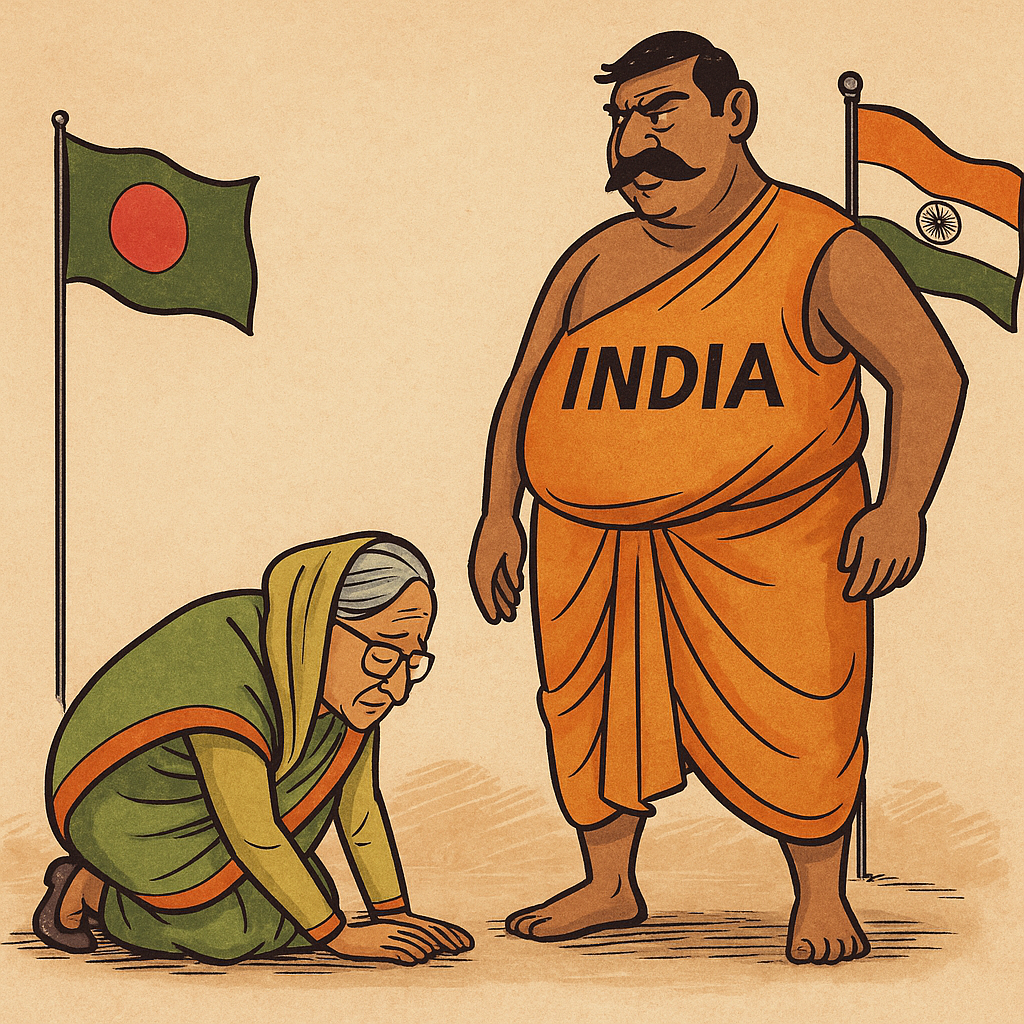

"Globally, we're talking about the largest mass migration in human history," says Maj. Gen. Muniruzzaman, a charismatic retired army officer who presides over the Bangladesh Institute of Peace and Security Studies in Dhaka. "By 2050 millions of displaced people will overwhelm not just our limited land and resources but our government, our institutions, and our borders." Muniruzzaman cites a recent war game run by the National Defense University in Washington, D.C., which forecast the geopolitical chaos that such a mass migration of Bangladeshis might cause in South Asia. In that exercise millions of refugees fled to neighboring India, leading to disease, religious conflict, chronic shortages of food and fresh water, and heightened tensions between the nuclear-armed adversaries India and Pakistan.

Such a catastrophe, even imaginary, fits right in with Bangladesh's crisis-driven story line, which, since the country's independence in 1971, has included war, famine, disease, killer cyclones, massive floods, military coups, political assassinations, and pitiable rates of poverty and deprivation—a list of woes that inspired some to label it an international basket case. Yet if despair is in order, plenty of people in Bangladesh didn't read the script. In fact, many here are pitching another ending altogether, one in which the hardships of their past give rise to a powerful hope.

For all its troubles, Bangladesh is a place where adapting to a changing climate actually seems possible, and where every low-tech adaptation imaginable is now being tried. Supported by governments of the industrialized countries—whose greenhouse emissions are largely responsible for the climate change that is causing seas to rise—and implemented by a long list of international nongovernmental organizations (NGOs), these innovations are gaining credence, thanks to the one commodity that Bangladesh has in profusion: human resilience. Before this century is over, the world, rather than pitying Bangladesh, may wind up learning from her example.

More than a third of the world's people live within 62 miles of a shoreline. Over the coming decades, as sea levels rise, climate change experts predict that many of the world's largest cities, including Miami and New York, will be increasingly vulnerable to coastal flooding. A recent study of 136 port cities found that those with the largest threatened populations will be in developing countries, especially those in Asia. Worldwide, the two cities that will have the greatest proportional increase in people exposed to climate extremes by 2070 are both in Bangladesh: Dhaka and Chittagong, with Khulna close behind. Though some parts of the delta region may keep pace with rising sea levels, thanks to river sediment that builds up coastal land, other areas will likely be submerged.

But Bangladeshis don't have to wait decades for a preview of a future transformed by rising seas. From their vantage point on the Bay of Bengal, they are already facing what it's like to live in an overpopulated and climate-changed world. They've watched sea levels rise, salinity infect their coastal aquifers, river flooding become more destructive, and cyclones batter their coast with increasing intensity—all changes associated with disruptions in the global climate.

On May 25, 2009, the people of Munshiganj, a village of 35,000 on the southwest coast, got a glimpse of what to expect from a multifoot rise in sea level. That morning a cyclone, called Aila, was lurking offshore, and its 70-mile-an-hour winds sent a storm surge racing silently toward shore, where the villagers, unsuspecting, were busy tending their rice fields and repairing their nets.

Shortly after ten o'clock Nasir Uddin, a 40-year-old fisherman, noticed that the tidal river next to the village was rising "much faster than normal" toward high tide. He looked back just in time to see a wall of brown water start pouring over one of the six-foot earthen dikes that protect the village—its last line of defense against the sea.

Within seconds water was surging through his house, sucking away the mud walls and everything else. His three young daughters jumped onto the kitchen table, screaming as cold salt water swirled around their ankles, then up to their knees. "I was sure we were dead," he told me months later, standing in shin-deep mud next to a pond full of stagnant green water the color of antifreeze. "But Allah had other plans."

As if by a miracle, an empty fishing boat swept past, and Uddin grabbed it and hoisted his daughters inside. A few minutes later the boat capsized, but the family managed to hang on as it was tossed by waves. The water finally subsided, leaving hundreds of people dead along the southwest coast and thousands homeless. Uddin and most of his neighbors in Munshiganj decided to hunker down and rebuild, but thousands of others set out to start a new life in inland cities such as Khulna and Dhaka.

Thousands of people arrive in Dhaka each day, fleeing river flooding in the north and cyclones in the south. Many of them end up living in the densely populated slum of Korail. And with hundreds of thousands of such migrants already, Dhaka is in no shape to take in new residents. It's already struggling to provide the most basic services and infrastructure.

Yet precisely because Bangladesh has so many problems, it's long served as a kind of laboratory for innovative solutions in the developing world. It has bounced back from crisis after crisis, proving itself far more resourceful than skeptics might have guessed. Dhaka is home to BRAC, the largest nonprofit in the developing world, held up as a model for how to provide basic health care and other services with an army of field-workers. Bangladesh also produced the global micro-finance movement started by Nobel Peace laureate Muhammad Yunus and his Grameen Bank.

And believe it or not, it's a population success story as well. To whittle its high birthrate, Bangladesh developed a grassroots family-planning program in the 1970s that has lowered its fertility rate from 6.6 children per woman in 1977 to about 2.4 today—a historic record for a country with so much poverty and illiteracy. Fertility decline has generally been associated with economic improvement, which prompts parents to limit family size so they can provide education and other opportunities to their children. But Bangladesh has been able to reduce fertility despite its lack of economic development.

"It was very hard in the beginning," says Begum Rokeya, 42, a government health worker in the Satkhira District who's made thousands of home visits to persuade newlywed couples to use contraception and plan their family's size. "This is a very conservative country, and men put pressure on women to have lots of children. But they began to see that if they immunized their kids, they wouldn't need to have a bunch of babies just so a few would survive. They like the idea of fewer mouths to feed."

Working in partnership with dozens of NGOs, Bangladesh has made huge strides in educating women and providing them with economic opportunities; female work-participation rates have doubled since 1995. Its economy is growing, helped by its garment-export industry. And Bangladesh has managed to meet an important UN Millennium Development Goal: Infant mortality dropped dramatically between 1990 and 2008, from 100 deaths per 1,000 births to 43—one of the highest improvement rates among low-income countries.

In Dhaka such successes are dwarfed by the overwhelming poverty and the constant influx of villagers, prompting organizations, including BRAC, to get involved in helping village people figure out how to survive in a deteriorating environment. "Our goal is to prevent people from coming to Dhaka in the first place, by helping them adapt and find new ways of making a go of it in their villages," says Babar Kabir, head of BRAC's climate change and disaster management programs. "Big storms like Aila uproot them from the lives they know."

Ibrahim Khalilullah has lost track of how many times he's moved. "Thirty? Forty?" he asks. "Does it matter?" Actually those figures might be a bit low, as he estimates he's moved about once a year his whole life, and he's now over 60. Somehow, between all that moving, he and his wife raised seven children who "never missed a meal," he says proudly. He's a warm, good-natured man, with gray hair cut short and a longish gray beard, and everything he says has a note of joy in it.

Khalilullah is a char dweller, one of the hundreds of thousands of people who inhabit the constantly changing islands, or chars, on the floodplains of Bangladesh's three major rivers—the Padma, Jamuna, and Meghna. These islands, many covering less than a square mile, appear and vanish constantly, rising and falling with the tide, the season, the phase of the moon, the rainfall, and the flow of rivers upstream. Char dwellers will set out by boat to visit friends on another char, only to find that it's completely disappeared. Later they will hear through the grapevine that their friends moved to a new char that had popped up a few miles downstream, built their house in a day, and planted a garden by nightfall. Making a life on the chars—growing crops, building a home, raising a family—is like winning an Olympic medal in adaptation. Char dwellers may be the most resilient people on Earth.

There are tricks to living on a char, Khalilullah says. He builds his house in sections that can be dismantled, moved, and reassembled in a matter of a few hours. He always builds on a raised platform of earth at least six feet high. He uses sheets of corrugated metal for the outside walls and panels of thatch for the roof. He keeps the family suitcases stacked neatly next to the bed in case they're needed on short notice. And he has documents, passed down from his father, that establish his right to settle on new islands when they emerge—part of an intricate system of laws and customs that would prevent a million migrants from the south, say, from ever squatting on the chars. His real secret, he says, is not to think too much. "We're all under pressure, but there's really no point to worry. This is our only option, to move from place to place to place. We farm this land for as long as we can, and then the river washes it away. No matter how much we worry, the ending is always the same."

Even in the best of times, it's a precarious way of life. And these are not the best of times. In Bangladesh climate change threatens not just the coast but also inland communities like Khalilullah's. It could disrupt natural cycles of precipitation, including monsoon rains and the Tibetan Plateau snowfall, both of which feed the major rivers that eventually braid their way through the delta.

But precisely because the country's geography is prone to floods and cyclones, Bangladeshis have gotten a head start on preparing for a climate-changed future. For decades they have been developing more salt-resistant strains of rice and building dikes to keep low-lying farms from being flooded with seawater. As a result, the country has actually doubled its production of rice since the early 1970s. Similarly its frequent cyclones have prompted it to build cyclone shelters and develop early-warning systems for natural disasters. More recently various NGOs have set up floating schools, hospitals, and libraries that keep right on functioning through monsoon season.

"Let me tell you about Bangladeshis," says Zakir Kibria, 37, a political scientist who serves as a policy analyst at Uttaran, an NGO devoted to environmental justice and poverty eradication. "We may be poor and appear disorganized, but we are not victims. And when things get tough, people here do what they've always done—they find a way to adapt and survive. We're masters of 'climate resilience.'"

Muhammad Hayat Ali is a 40-year-old farmer, straight as bamboo, who lives east of Satkhira, about 30 miles upstream of the coast but still within range of tidal surges and the salinity of a slowly rising sea. "In previous times this land was juicy, all rice fields," Ali says, his arm sweeping the landscape. "But now the weather has changed—summer is longer and hotter than it used to be, and the rains aren't coming when they should. The rivers are saltier than before, and any water we get from the ground is too salty to grow rice. So now I'm raising shrimps in these ponds and growing my vegetables on the embankments around them." A decade ago such a pond would have been a novelty; now everyone, it seems, is raising shrimps or crabs and selling them to wholesalers for shipment to Dhaka or abroad.

Sometimes, though, adaptations backfire. Throughout southern Bangladesh, villages and fields are shielded from rivers by a network of dikes built by the government with help from Dutch engineers in the 1960s. During floods the rivers sometimes overflow the dikes and fill the fields like soup bowls. When the flood recedes, the water is trapped. The fields become waterlogged, unusable for years at a time.

Decades ago things got so bad in Satkhira—so many fields were waterlogged, so many farmers out of work—that members of the local community used picks and shovels to illegally cut a 20-yard gap in an embankment, draining a huge field that had been waterlogged for nearly three years. In doing so, they were emulating Bengali farmers of earlier times, who periodically broke their embankments and allowed river water to enter their fields, rising and falling with the tides, until the deposited sediment raised the level of the land. But this time the villagers were charged with breaking the law.

Then a funny thing happened. The field, which had been left open, acquired tons of sediment from the river and grew higher by five or six feet. The river channel deepened, and fishermen began to catch fish again. Finally a government study group came to survey the situation and wound up recommending that other fields be managed the same way. The villagers were vindicated, even hailed as heroes. And today the field is covered with many acres of rice.

"Rivers are a lifeline for this region, and our ancestors knew that," Kibria says as he walks an embankment. "Opening the fields connects everything. It raises the land level to make up for the rise in sea level. It preserves livelihoods and diversifies the kinds of crops that we can grow. It also keeps thousands of farmers and fishermen from giving up and moving to Dhaka."

But every adaptation, no matter how clever, is only temporary. Even at its sharply reduced rate of growth, Bangladesh's population will continue to expand—to perhaps more than 250 million by the turn of the next century—and some of its land will continue to dissolve. Where will all those people live, and what will they do for a living?

Many millions of Bangladeshis are already working abroad, whether in Western countries, in places such as Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates, or in India, where millions fled during Bangladesh's 1971 war of independence against Pakistan and never returned. Millions more have slipped across the frontier in the decades since, prompting social unrest and conflict. Today India seems determined to close and fortify its border, girding against some future mass migration of the type hypothesized in Washington. It's building a 2,500-mile security fence along the border, and security guards have routinely shot people crossing illegally into India. Interviews with families of victims suggest that at least some of the dead were desperate teenagers seeking to help their families financially. They had been shot smuggling cattle from India, where the animals are protected by Hinduism, to Muslim Bangladesh, where they can fetch up to $40 a head.

But if ten million climate refugees were ever to storm across the border into India, Maj. Gen. Muniruzzaman says, "those trigger-happy Indian border guards would soon run out of bullets." He argues that developed countries—not just India—should be liberalizing immigration policies to head off such a chilling prospect. All around Bangladesh bright, ambitious, well-educated young people are plotting their exit strategies.

And that's not such a bad idea, says Mohammed Mabud, a professor of public health at Dhaka's North South University and president of the Organization for Population and Poverty Alleviation. Mabud believes that investing in educating Bangladeshis would not only help train professionals to work within the country but also make them desirable as immigrants to other countries—sort of a planned brain drain. Emigration could relieve some of the pressure that's sure to slam down in the decades ahead. It's also a way to bolster the country's economy; remittances sent back by emigrants account for 11 percent of the country's GDP. "If people can go abroad for employment, trade, or education and stay there for several years, many of them will stay," he says. By the time climate change hits hardest, the population of Bangladesh could be reduced by 8 to 20 million people—if the government makes out-migration a more urgent priority.

For now, the government seems more interested in making climate adaptation a key part of its national development strategy. That translates, roughly, into using the country's environmental woes as leverage in persuading the industrialized world to offer increased levels of aid. It's a strategy that's helped sustain Bangladesh throughout its short, traumatic history. Since independence, it has received tens of billions of dollars in international aid commitments. And as part of the accord produced at the United Nations Climate Change Conference in Copenhagen in 2009, nations of the developed world committed to a goal of $100 billion a year by 2020 to address the needs of poor countries on the front lines of climate change. Many in Bangladesh believe its share should be proportionate to its position as one of the countries most threatened.

"Climate change has become a kind of business, with lots of money flying around, lots of consultants," says Abu Mostafa Kamal Uddin, former program manager for the government's Climate Change Cell. "During the global financial meltdown, trillions of dollars were mobilized to save the world's banks," he says. "What's wrong with helping the poor people of Bangladesh adapt to a situation we had nothing to do with creating?"

Two years after the cyclone, Munshiganj is still drying out. Nasir Uddin and his neighbors are struggling to wring the salt water out of their psyches, rebuild their lives, and avoid being eaten by the tigers that prowl the village at night, driven from the adjacent Sundarbans mangrove forest in search of easy prey. Attacks have risen as population and environmental pressures have increased. Dozens of residents around Munshiganj have perished or been wounded in recent years—two died the week I was there—and some of the attacks occurred in broad daylight.

"It's bad here, but where else can we go?" Uddin says, surveying the four-foot-high mud platform where he's planning to rebuild his house with an interest-free loan from an NGO. This time he's using wood, which floats, instead of mud. The rice fields around his house are full of water, much of it brackish, and most local farmers have begun raising shrimps or crabs in the brine. Deep wells in the village have gone salty too, he says, forcing people to collect rainwater and apply to NGOs for a water ration, which is delivered by truck to a tank in the village and carried home in aluminum jugs, usually balanced on the heads of young women. "You should take a picture of this place and show it to people driving big cars in your country," says Uddin's neighbor Samir Ranjan Gayen, a short, bearded man who runs a local NGO. "Tell them it's a preview of what South Florida will look like in 40 years."

As the people of Munshiganj can attest, there's no arguing with the sea, which is coming for this land sooner or later. And yet it's hard to imagine millions of Bangladeshis packing up and fleeing en masse to India, no matter how bad things become. They'll likely adapt until the bitter end, and then, when things become impossible, adapt a little more. It's a matter of national mentality—a fierce instinct for survival combined with a willingness to put up with conditions the rest of us might not.

Abdullah Abu Sayeed, a literacy advocate, explains it this way: "One day I was driving on one of the busiest streets in Dhaka—thousands of vehicles, all of them in a hurry—and I almost ran over a little boy, no more than five or six years old, who was fast asleep on the road divider in the middle of traffic. Cars were whizzing by, passing just inches from his head. But he was at peace, taking a nap in some of the craziest traffic in the world. That's Bangladesh. We are used to precarious circumstances, and our expectations are very, very low. It's why we can adapt to just about anything."

অনুগ্রহ করে অপেক্ষা করুন। ছবি আটো ইন্সার্ট হবে।

অনুগ্রহ করে অপেক্ষা করুন। ছবি আটো ইন্সার্ট হবে।